Sosia d’ombra

16 marzo - 21 aprile 2003, Castello Visconteo, Trezzo sull’Adda

3 - 22 aprile 2004, Cascina Roma, San Donato Milanese

Spesso il grumo di abitudini e di ripetizioni in cui viviamo non permette di accorgerci che il mondo nel quale siamo stati generati è un'immensa fucina di segni: ogni gesto, ogni evento, ogni cosa è un segno.

Interpretare e reinterpretare sempre e ogni volta daccapo i segni che popolano il nostro mondo è compito dell'arte che, se è veramente tale, è anche in grado di rivelarne continuamente l'inesauribile possibilità progettuale.Questa avventura della forma che diventa principio di comprensione sfida ogni sistema di informazione ed è più profonda di ogni esplicazione attraverso la parola essendo il punto dove si danno convegno intelletto e passione.

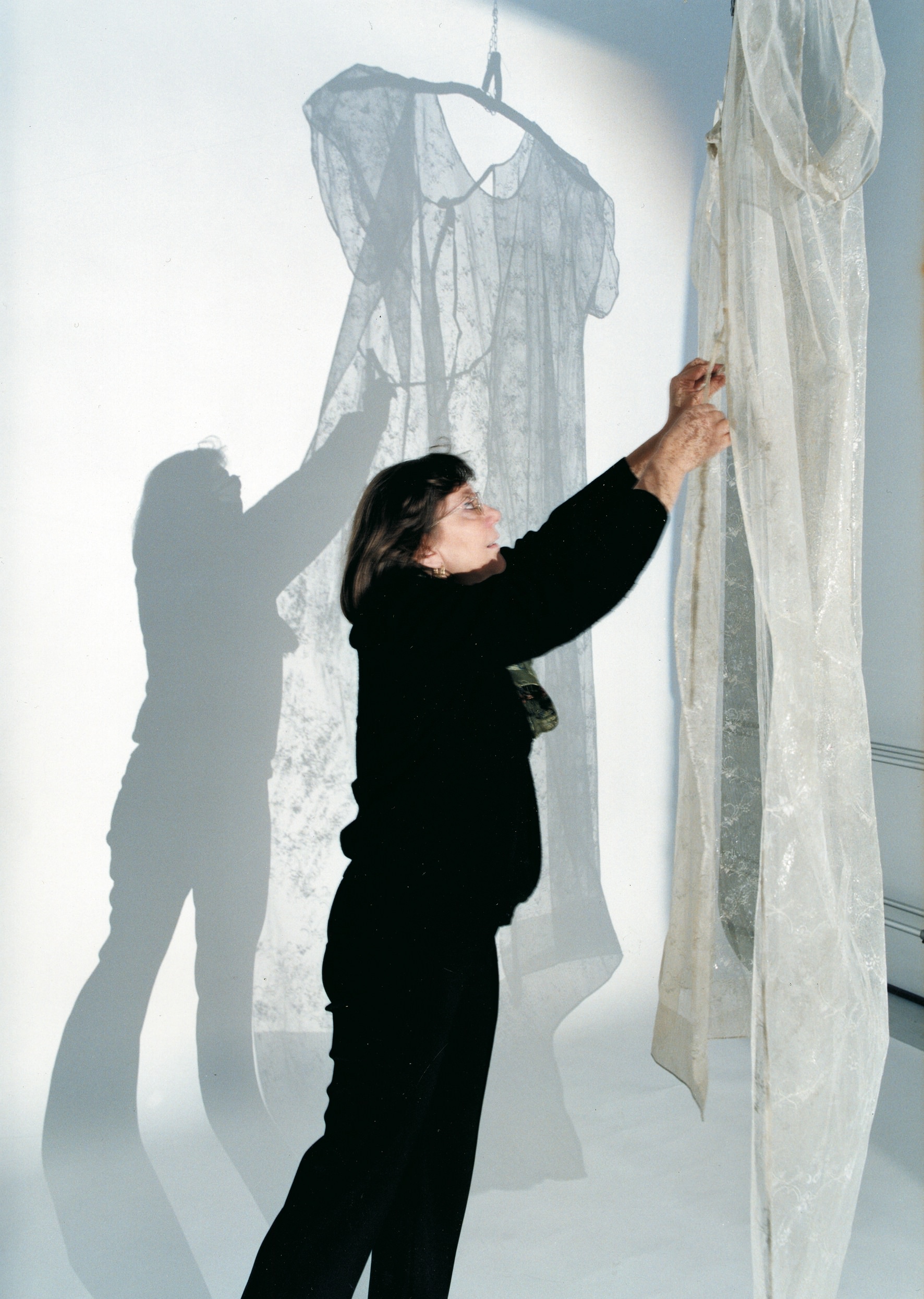

Avvicinandomi per la prima volta criticamente al lavoro di Sara Montani, che in questa mostra personale intitolata Sosia d'Ombra espone un notevole numero di opere, di diversa natura, ma riferibili a un'unica ricerca, mi ha fortemente impressionato la sua energia progettuale. Si tratta della capacità di mettere in campo, attraverso gli esiti più compiuti del suo lavoro d'artista, la straordinaria possibilità di riconfigurazione dell'esperienza nel suo travaglio di diventare trasmissione culturale e comunicazione.

All'origine sta infatti un vissuto: il disagio della spoliazione dei propri indumenti durante un ricovero per indossare un'anonima camicia ospedaliera, la cancellazione della persona nell'ingigantirsi dell'emergenza della malattia che diventa il nuovo soggetto referente.

Di qui l'inizio di una rielaborazione artistica della Montani che si dipana in ogni direzione altezza, larghezza, profondità, quasi a tracciare le coordinate che ne identificano il suo possibile prender forma o annientarsi, il suo espandersi e trasformarsi, il suo inverarsi cambiando registro.

Una serie di indumenti prende corpo o, del corpo, diventa la metafora poetica attraversandone il possibile spessore esistenziale, toccandone le diverse età della vita. La camicia ospedaliera si materializza tridimensionalmente in una trasparente veste leggera che porta l'impronta di un motivo floreale solidificato dall'artista attraverso un sapiente processo in vetroresina, un tessuto un tessuto antico che racconta di ambienti domestici accarezzati dalla luce che vi entra filtrata. Appesa al ramo, divenuto gruccia, questa veste ricorda anche l'abito da sposa, ma ha un suo sosia, l'ombra che, proiettandosi imponente sul muro, ne rivela l'inquietante ambivalenza, l'essere attivo e passivo di ogni situazione, la possibilità di trasformare e di essere trasformata, di suggerire un dentro e un fuori rispetto alle cose, di considerare la sostanza e il nulla che rappresentano, la naturalità e l'artificialità cui alludono.

Quasi a provare la verità di questo assunto che attiene alla ricerca dell'identità e al gioco in essa della libertà, nel senso più personale e ugualmente universale, la Montani prova a procedere in più direzioni.

Introduce un altro indumento, un'enorme camicia di forza con le sue lunghe maniche e i suoi lacci lasciati liberi sul pavimento, come a indicarne l'inutilità e la contraddizione tradotta nella civetteria assurda del pizzo vetrificato che le dà forma.

E per associazione altre "vesti" entrano nel confronto, il camicino e la benda ombelicale del neonato, il perizoma-reggicalze, la cravatta: "vesti" che avvolgono il corpo indifeso e "vesti"

che si scelgono per il loro potere di seduzione, comunque, tutte caratterizzate dall'essere o possedere lacci.

Per la Montani il processo non si chiude nell'unità della singola opera, ma travalica il confine in un diluvio di domande che il percorso artistico evidenzia attraverso una ricerca curiosa e sollecita nelle pieghe della materia che, abilmente manipolata, è in grado di rivelare risposte.

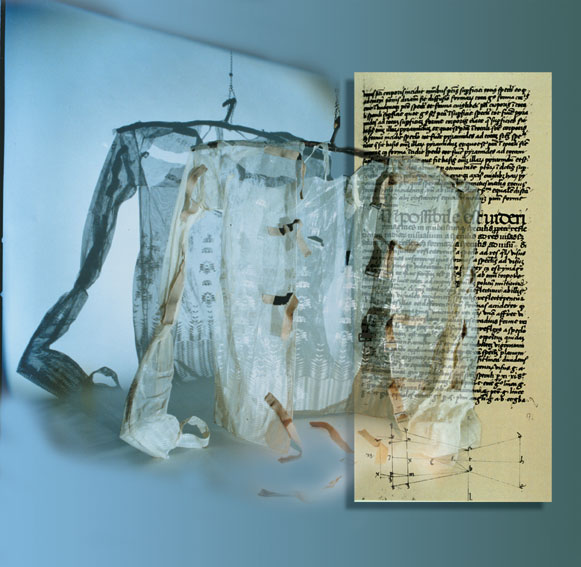

La Montani trasferisce gli oggetto sulla lastra per contatto, la loro impronta sul rame, sulla masonite, opera con la cera molle su zinco, utilizza il torchio calcografico e tutte le matrici possibili. Ancora elabora le immagini al computer e le pone in dialogo con i capolavori del passato, il battistero di Pisa, l'Annunciazione di Simone Martini, ma anche con i testi scritti universalmente famosi, come quello sulla prospettiva, recuperando i fili di un esercizio ininterrotto che non si stanca di attraversare la quotidianità dell'esperienza con le categorie della storia dell'arte e la storia con quelle dell'esperienza.

Il possibile sospinge il reale oltre la sua datità e lo avvolge in un alone di immaginazione che non cessa d'inquietarlo, di sospingerlo e di prolungarlo in un ulteriore significato.

Cecilia De Carli

Chi si sente nudo?

L'abito, quello di tutti i giorni, o della festa, dell' "io sono così", del "non sai chi sono io", o del "così mi sento", è una protesi acquisita, inconscia, una pelle che non si stacca. Gli strati sulla nostra mente sono molti più di quelli che hanno coperto ii nostri corpi.

Codici, messaggi, maschere, credenziali, identità, aspettative, promesse, fughe, tentativi, contrattazioni, domande... E anche la nudità diventa glamour patinato, forma costruita, credito.

Così il senso di sè, delle cose, degli altri è sempre vestito, forse sempre più vestito, mano a mano che la liberazione, la continua sostituzione degli strati acquisiti metteranno a nudo il manichino, insieme al sottile potere che lo vincola.

Così l'ambivalenza non si risolve. Se l'abito esprime, presenta, seduce, libera i corpi nel serraglio sociale, insieme copre, difende, protegge.

E appena offriamo il sorriso soddisfatto e sicuro di chi si sente nella pelle giusta, già abbiamo perduto il nostro volto, la comprensibilità del gioco, ma ancor più del giocatore, di noi.

Non se ne esce, perché se anche ci vestissimo di stracci o come vent'anni fa, la definizione del "guarda quello", più o meno manipolata e consapevole, ci raggiungerebbe inesorabile, limitando il nostro spazio, i nostri sentieri.

Allora sì, che siano segni incerti, veli in dissolvenza, ombre a vestirci nudi; indefinite incertezze, come silenzi, in cui abbandonarsi in meditazione. Il richiamo dell'indistinto come uscita, come possibilità dell'inizio, anche se su uno sfondo conosciuto, o ambiguo.

Beppe Mosconi

Quite often the bunch of habits and repetitions we live in doesn’t let us realize that the world we came from is a huge source of signs: any gesture, any event, anything is a sign. Interpreting and reinterpreting any time from the beginning signs that inhabit our world is an art task and if it’s a real one, it can continuously reveal its never ending projecting capacity.

This shape adventure, working as an understanding structure, challenges any information system and it’s deeper than any words explication, because it’s where intellect and passion meet.

For the first time critically approaching Sara Montani’s artworks, I’ve really felt its projecting power: in Montani’s exhibition, titled Shadow’s double, lots of items are shown, each of them characterized by a different nature but all leading to the same research. That power refers to the amazing capability of experience resetting itself to become cultural transmission and communication.

At the beginning there’s something lived: the uncomfortable experience of the spoliation of your garments during an hospitalization in order to wear an anonymous hospital shirt, the human being deleted by the terrific growth of the disease, becoming the new referring subject.

From here the beginning of another artistic elaboration in Montani’s art world that unfolds itself in any direction, height, width, depth, almost capable to trace its perimeter in order to identify its taking shape or annihilating, its spreading and turning, its becoming true changing its ways. A set of garments embodies, or becomes the poetic metaphor of the body, passing through its existential thickness, touching various life’s ages. Hospital shirt materializes itself into a three dimension diaphanous light garment bearing a flower-like mark print: it has been hardened by the artist through an expert fibreglass technique, an old cloth telling about home spaces, caressed by the incoming filtered light. Hung on the branch, now a dress-hanger, this garment reminds of a wedding – dress also, but it has a double, the shadow that, impressively reflecting on a wall, reveals its alarming ambiguity: that includes being active or passive in any situation, transforming and being transformed, suggesting an in – group and out – group feeling, considering the substance and the nothingness that things represent, naturalness and artificiality they refer to.

Just to test the veracity of this concept referring to the identity research and freedom play inside it, Montani attempts to proceed in different directions.

Another item is introduced, a huge straitjacket with its long sleeves and its long nooses left on the floor, as to show its uselessness and contradiction expressed into the meaningless coquetry of the vitrified lace that shapes it.

Other garments are taken into account, baby’sumbilical bandage, loincloth – garter belt, tie: garments that wrap up the harmless body and garments chosen because of their appeal power: all of them characterized by being or having nooses.

Dresses hung in the art world recall us other well known artworks like Lingerie Counter (1962) by Claes Oldenburg or Pink Days and Blue Days (1997) by Louise Bourgeois, two installations strongly stimulating that tell parallel stories. Oldenburg lingerie items, also them hardened, but by chalk, and enamelled, reflect human beings: they are “historical fetishes and monuments” of time, public referents of its aggressiveness, according to the form metamorphosis intuition that is artist’s password, while dresses by Bourgeois, hung on thigh - bones, explore mysteries and dramas of artist‘s childhood.

In Montani’s art world the process doesn’t close in the individuality of a single artwork, but goes beyond the border in a flood of questions stressed by the artistic process through a prompt research that, in the folds ofthe material, skilfully worked, is able to reveal answers.

Montani brings objects on the plate, their print on copper, on masonite: sheworks with soft wax on zinc and makes use of copperplate press and of any available matrix. Besides she computes images and put them in a dialoguewith past masterpieces, like the Battistero in Pisa, L’annunciazione by Simone Martini, but also with written works world wide known, like the one on perspective: this way she traces back to a never ending pattern, crossing and matching every day life categories with art history ones and vv.

Possibility pushes reality beyond its ‘dataness’ and wraps it in a halo of fantasy that does not stop to worry it, to drive it forward and to last it into a further meaning. Along this concept the philosopher Dino Formaggio, writing a terrific chapter about the projecting capability of art (Arte, Isedi, Milano 1973), states that “while sensible traces actual paths that lead to something sure, at the same time it traces paths continuously evolving, mainly fantastic,regarding the projecting capacity and art also. Here we found the sensible birth of possible becoming temporal, of signs miming worlds senses often unachievable, to sum up with “the invisible giving meaning to the sensible, to the extent that invisible embodies, taking shape, body and sign.”.

Sara Montani’s art world comes up with this philosophic idea because of its direct will to manipulate reality: almost as a rule of her “making art” to give meaning when differences and opposites meet, of her interpreting search that passes through the projection of individuality, but that opens itself strongly to a formative exercise and to a formative intentionality, offering a free port where put upside down rules that state social conformity and ego annihilating / deifying, becoming a way to win in a projecting way – not de facto, death.

Cecilia De Carli

Chi si sente nudo?

Who feels naked? The vest, the daily one, or the Sunday – dress, the ”I’m like that”, the “who do you think I’m”, or the “I feel like that”, it’s an acquired and unconscious prosthesis, a not removable skin. Layers left on our mind are many more than the ones that have covered our bodies.

Codes, messages, masks, credentials, identities, expectations, promises, escapes, attempts, negotiations, questions... And nudity becomes glamour, built shape, credit. Self sense , sense of things, of others, is always dressed, maybe more and more dressed, as far as liberation, the continuous changing of layers acquired will lay the dummy bare, together with the subtle power that ties it up. Ambiguity cannot be solved this way.

If dress expresses, shows, seduces and frees bodies in the social seraglio, at the same time it covers, defends, protects.

And as soon as we offer our smile fulfilled and firm like someone feeling comfortable, we've already lost our face, the understanding of the game, but even more of the player, of ourselves.

It's impossible to find a way out, because even if we dress in rags or like twenty years ago, the expression 'look at that one', more or less manipulated and conscious, will reach us relentlessly, restricting our space, our routes.Then ok, being they uncertain sings, dissolving veils, shadows dressing us naked; indefinite uncertainties, like silences, where you can lose yourself in meditation. The recall of the vague as a way out, as a chance of the beginning, even if on a known or an ambiguous background.

Then we'll dress up or not; it doesn't matter. Dress coming and going: it stops, flies, arrives.

Taking on, crossing, subverting the shadiness, one inside another one, the ambiguity of a mutual belonging.

Then someone could reach us where we'll actually are.

Beppe Mosconi